- Home

- E. L. Shen

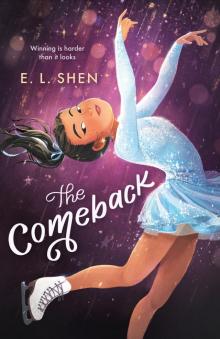

The Comeback

The Comeback Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

About the Author

Copyright Page

Thank you for buying this

Farrar, Straus and Giroux ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on the author, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For my family—my greatest champions.

Mornings

Girls who skate always think they’re the next Olympians: If I just nail that Axel and tweak that three-turn, I’ll win gold. I’ll become a star. I’ll be on TV. I’ll make America proud. You have to be fifteen to be eligible for the Olympics. I’ve got three more years to go. But I don’t just think I’ll get there. I promise I will.

“Maxine Chen! Arms up!”

Coach Judy only uses my full name when she’s annoyed at me. Pulling me out of my 6:00 a.m. daydreams, she points at my twiggy arms, which have lowered to my sides as I skate around the rink. An eagle, she always reminds me, that’s what you should look like. I grin, wildly flapping my arms as I drift across the ice. Judy rolls her eyes.

Morning curves through the thin line of windows tracing the rink’s walls. Outside, shopkeepers on Main Street will soon unlock their doors, offering tourists refrigerator magnets and hooded Adirondack sweatshirts. Kayakers will take out their boats for a final paddle before the lake freezes over. The mountains will stretch from the shadows and graze the horizon. Life will begin. But for now, I only hear the skid of my skates as they power down the ice. This is my favorite form of silence. This is where the magic happens.

I flap my eagle wings all the way to Judy, who is simultaneously scowling and chugging a thermos of black coffee. She may be the greatest skating coach in all of Lake Placid, but she is the worst morning person.

“I can fly higher than an eaaaaaagle,” I sing to her. “Oh, you are the wind beneath my wiiiiiiiiiiiiiings.”

I end my serenade with a toe pick in the ice, arms out, head thrown back. I close my eyes for dramatic effect.

“I think this is how I should end my free skate.”

Even though I can’t see her, I can tell she’s smirking at me.

“If you start cawing, I will take you off the ice,” she says.

I swing my head back to her, flipping my ponytail over my shoulder.

“Why, Coach, I would never.”

Judy sets down her thermos and shakes her head.

“You’re ridiculous,” she tells me, but a hint of a smile appears on her lips. “Now let’s see that double Axel.”

I groan. The double Axel is my worst jump. It’s the only one where you have to take off facing forward. Then you pull your whole weight into the air and rotate around not once, but two and a half times, until somehow you manage to land on your right foot, arms out, left leg extended, triumphant. Honestly, I don’t see why figure skaters aren’t considered superheroes.

I take a deep breath and start my backward crossovers. I know without looking that Judy is practically boring holes into my skates, waiting for them to push off. I envision her face as nine middle-age judges squinting at me, glasses sliding down their noses, parkas zipped up to their necks, writing down scores that could make or break my entire skating career.

You got this, I tell myself. I imagine Mirai Nagasu before me—she’s one of my favorite skaters, partly because we’re both Asian American. But what makes her really special is that she’s the first American woman to land a triple Axel at the Olympics (that’s three and a half rotations in the air, which lends her true superhero status). I think of her fist pumped in the sky as she finished her flawless routine, her coach jumping up and down by the boards, the crowd screaming, the tears on her face as she finally delivered.

I push off.

My body feels heavy in the air.

And then it feels like nothing at all, like I’m on one of those teacups from Magic Island Park that’s just turning and turning until it comes to a rest.

Before I know it, I’m back on the ice, arms out, leg perfectly stretched. I slow to a stop and look up at Judy.

She’s beaming.

“If you do exactly that at regionals,” she says, “you’ll definitely medal.”

It’s my turn to pump my fist in the air. I may not be Mirai Nagasu yet, but just you wait.

Self-Portrait

Victoria is mad at me again. I know because she’s peering around the side of my open locker door, a massive pout plastered on her face.

“You’ve got lip gloss on your chin,” I tell her.

She sniffs, rubbing at her skin and streaking her finger with sticky pink.

“And you never answered my text,” she accuses. Her eyes narrow.

I crouch to stuff my skate bag into my locker.

“No.” I shake my head. “I didn’t get a text.”

Victoria’s messages are hard to miss. She put her name in my phone with five heart emojis, six dancing ladies, and three snowflakes so that my notifications explode with a confetti of color. We’ve been friends since we were eight, mostly because our moms work at the same pharmacy and thought we’d have fun building castles in the makeshift sandpit by the lake. Now, though, she’s busy with drama club and softball while I’m permanently stuck on the ice until my thighs burn and my hands are numb. The sand dunes from our childhood have long washed away.

Victoria jabs my shoulder. “You did,” she says. “Go look.”

“Fine.”

I dig out my phone from the bottom of my backpack. Sure enough, buried under four texts from my mom (How was practice? Do you have enough lunch money? What time should I pick you up from the rink? Hello??) is a note from Victoria alongside a bajillion smiley faces: Come over after school 2morrow?

My shoulders droop. “Ugh, Vic, I’m sorry I didn’t see this.”

“Whatever,” she says. She adjusts her headband and sniffs. “It’s fine. Can you come, though? My sister bought me face masks for my birthday that we can try.”

I want to. I really do. But regionals are only three and a half weeks away. I need to head straight to the rink once the final bell rings. Luckily, it’s right next to school, so Mom and Dad let me walk there by myself (although they insist on picking me up after practice because I’m not allowed to walk home in the dark). That’s the beauty of living in a place that prides itself on being a former Olympic Village. The multi-acre arena isn’t just the center of my world—it’s the center of our entire town. The huge stone building is flanked with international flags and pressed green grass. It symbolizes the excellence of our facilities and our athletes. All the more pressure to nail my routines.

“I can’t,” I finally say. I look down, fumbling with my backpack strap. “I have practice.”

Victoria groans. “Practice, practice, blah, blah, blah.”

She takes her hand and forms a talking mouth that almost jabs me in the eyeballs. I can’t help but laugh, dodging her fingernails before slamming my locker shut to face her.

My jaw hangs open. Victoria, who usually sports flat-ironed hair and fashion-forward turtlenecks, looks like a giant blueberry. Her sweatshirt bubbles over her thighs and curls around her hands. On one side of the chest is the school mascot, a dragon. Embroidered in white cursive on the other is the name Macreesy.

&n

bsp; “What are you wearing?”

“Oh, this?”

Victoria smirks, holding out her arms like she’s modeling for a fashion show and not for the role of Violet from Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory.

“It’s Alex’s,” she tells me, her voice coated with glee.

I shake my head. “Why are you wearing Alex Macreesy’s sweatshirt?”

She shrugs, tossing her hair over her shoulder. “I was cold at lunch, so I took it.”

“And you never gave it back?”

She winks at me. “Of course not, silly.”

Gross. So this is a thing now? Alex isn’t exactly my favorite person in the world. Not only is he annoying in that way most boys are annoying, but he can also be kind of mean. Like the time he picked on a shy new girl for having a smelly lunch. Sure, he’s got side-swept hair and sort of muscular arms if you squint really hard, but those things don’t necessarily make him parade-around-in-his-sweatshirt material.

The bell rings, and Victoria and I shuffle to art class. Our sneakers squeak on the tile as we weave through throngs of sixth graders. Victoria starts jabbering about all the drama in Drama Club (there’s a lot), so I replay my double Axel from this morning in my head—my body as it swung through the air, the satisfying crunch of my blade when it hit the ice. I’ve already nailed my triple toe, so if I can land my double Axel cleanly sixteen more times, I’ll be sitting alongside the best of the best in the intermediate division. I can just see myself on the top of the podium, technical elements blown out of the park, biting into that gold medal. Mom cheering, teary eyed as usual, Dad waving his Jurassic video camera in my face. Even Judy will be proud. I close my eyes. The victory almost tastes real.

Victoria grabs my hand, jolting me from my fantasy as she drags me down the hall. Her pale, freckled skin contrasts against my tan wrists. Everyone at school looks like Victoria—ponytails bouncing against the napes of their ivory necks, blushes that turn their pasty cheeks bright red, light eyelashes on bright eyes. I’m the only one here who looks like, well, me. I don’t think about it too much, but sometimes, just the colors of our hands force me to remember. Mirror Lake may be blue, but our town is as white as the frost layering our windows during the first cold snap.

We reach the end of the hallway and Victoria swings open the door to the art room. I breathe in dried paint and sawdust and let the familiar air envelop me. I love art almost as much as I love skating, although I’m not nearly as good at it. When I do get into a rhythm, though, sometimes brushstrokes feel like crossovers on ice.

I grab a smock from the utility closet, squeeze into my seat, and admire the blank canvas resting on the easel before me. I’m antsy to start as the rest of the students settle in, but Mrs. Bettany takes her sweet time writing Self-Portrait on the blackboard. Then she spends fifteen minutes talking about technique and shading, and acrylic versus watercolor. By the time she’s done, half the class is smooshing their paintbrushes into their canvases and the other half somehow already has paint all over their smocks. Mrs. Bettany takes a slow, deep breath like she’s trying not to scream.

“Okay,” she says, “you can begin.”

Victoria squeals next to me, rolling up her blueberry sleeves. She dips her brush into purple paint and creates a diagonal line slicing her canvas in half. I wrinkle my nose.

“We’re supposed to be painting ourselves, Victoria,” I whisper.

Victoria grins. “I am painting myself. It’s called postmodernism.”

“A what now?”

Victoria waves her hand at me. “Never mind.” She paints a yellow line across the purple one, forming an X.

I have no idea what she’s talking about, so I stick with the basics, mixing white and brown to form my skin tone, followed by straight black hair and pink lips. I paint a little half circle for my nose instead of full-on nostrils, mostly because I suck at drawing noses and want to avoid accidentally making myself look like a pig.

I start on the eyes. As I paint, the wind blows through the branches of a maple outside, its leaves rustling against the windows, orange and red with pockets of green still left from the summer warmth. This time of year makes everything feel like it’s changing. Fall marks the beginning of skating competitions. This year, I know I’ll be on the podium. My pulse quickens with excitement.

That’s when I hear Alex Macreesy’s loud breath behind me. I turn, paintbrush hovering in the air.

At first, I think he’s here for Victoria, who is literally flinging her paintbrush in his face. But no, he’s staring at me, head cocked as he examines my portrait.

“Hi, Maxeeeeeeeeeeeen,” he says.

I try to ignore him and turn back to my painting.

“Hi.”

Alex steps closer so that his shirt is almost touching my shoulder.

“I think there’s something wrong with your painting,” he tells me.

“No, there isn’t.” I scan my portrait. It’s no masterpiece, but it isn’t terrible: a long, oval face, two happy eyes, hair draping the shoulders. I even dotted a couple of specks on my cheeks to represent my freckles. Mrs. Bettany would call that strong attention to detail.

“Alex, come look at my self-portrait,” Victoria calls from beside me, but he’s still standing over my shoulder, his mouth widening into a smile.

“Yeah, you made your eyes too big,” he says. “They should be narrower.”

I freeze. Finally, I can’t help but turn my face toward his. Alex lifts his hands, pulling at his own eyes, making them thin and slanted. Then he laughs, bumping my shoulder as he walks away.

My heart plummets. My paintbrush clatters back into the palette, now coated in a muddy brown. Victoria is giggling beside me, but she stops when she sees my face. She shifts in her seat.

“He’s just joking, Maxine.”

“Yeah,” I say, but I can barely croak out the word.

I keep my head to the ground, staring at my sneakers. My face is hot and tears puddle at the corners of my eyes. My thin, stupid eyes. My self-portrait stares back at me, the smirk I so proudly painted now mocking.

Keep it together, Maxine, I tell myself.

Victoria gets up to show off her portrait to Mrs. Bettany, swinging the canvas this way and that like she doesn’t have a care in the world.

I take a deep breath and try to conjure the image of Michelle Kwan—one of my favorite skaters—and her perfect spiral across the ice, her face aglow. I focus on her huge smile, her body the only movement on the rink, her gliding blades the only things that matter. It’s fine, I chant. It’s fine, it’s fine, it’s fine. I try so hard to focus on Michelle, but her image keeps flickering in my head. Instead, she’s replaced by Alex’s laughter echoing in my ears, over and over again.

Wounds

My skates feel like boulders and I’m pretty sure my ankles are blistering. After my tenth failed triple toe, I skid to the boards, kicking up flurries of snow in my wake. Judy is behind me, the big band number for my short program still blasting from her portable speaker.

She raises her eyebrows, a look I like to call “Maxine you are irritating me with that attitude so stop now.” The more raised her eyebrows, the more attitude I am apparently giving. Today, her eyebrows are practically lifting off her face.

I know she’s going to say that her other skaters, Sam and Fleur, are still on the ice, dutifully running through their step sequences until their parents call them home for dinner. Then she’ll tell me that I have twenty-five minutes still left in my practice session, so I better get my butt back out there, lest I waste my parents’ hard-earned money. And she’s right—that’s the worst part.

Up ahead, I can see Mom on the bleachers in her fleece, my gloves clutched in her fists. I hate wearing gloves on the ice, but she always brings them just in case I change my mind. Even from this far away, she looks worried. I sigh and pound my head against the boards. Judy places her hands on my shoulders.

“Maxine, c’mon,” she says slowly. “No matter how many tim

es you fall, you’ve got to get up.”

I snort. “Wow, Coach, you’re really laying on the cheese tonight.”

She spins me around so I’m facing her. The percussion now belts from the speaker tucked under her arm. This is the part where I should be showing off all my footwork, selling my pizzazz and flapper flamboyance to the crowd. Instead, I zip up my jacket all the way to my chin and try to bury my face in it.

“You were doing so well this morning,” Judy says. “What’s going on?”

“Nothing.”

“Well, that’s a lie.”

It sure is, but I’m not going to tell Judy about Alex Mac-greasy-face. As much as I try to block him out, his pink, gaping smirk still swirls in my mind—the way his fingers stretched the corners of his eyes into taut slits pinging back and forth against the backs of my own eyelids. I try to erase the images, but they linger.

I look up at Judy and say nothing. She shakes her head before releasing her hands from my shoulders.

“All right,” she relents, “go home and get some rest. I’ll see you tomorrow morning.”

She clicks off the music just as it bubbles over, a triumphant finish.

Now it is just me standing pitifully by myself. Judy calls out to Fleur to redo her camel spin.

I unlatch the gate. Mom is already halfway down the bleachers, rushing toward me. Her black hair bobs up and down against her coat, the crinkles in her forehead more pronounced than ever.

“Maxine—”

“Don’t worry about it,” I say.

She follows me into the locker room, arms crossed.

“What happened? You never get off the ice this early.”

I plop onto the bench, untangling my laces and ripping my skates from my feet.

“Nothing,” I say. “I’m just tired.”

I look down at the red stain seeping through my tights. Great. My ankles are bleeding. I yank off my tights, crumpling them into my bag. Like the walking first aid kit she is, Mom instantaneously whips out Band-Aids and gauze from her purse.

The Comeback

The Comeback