- Home

- E. L. Shen

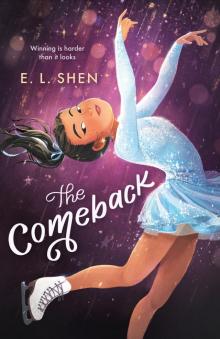

The Comeback Page 4

The Comeback Read online

Page 4

Okay, so I’ll start again. It can’t be this hard. Finally, I get it in a spot a quarter inch above my crease. Progress. Press the tweezers into the tape to adhere it firmly against your skin. I push and push until my eye feels like it is being jammed into its socket. At last, I face my reflection in the mirror.

Everything feels super weird, like my eye is bent in this strange direction that it doesn’t like. The worst part is: I look even more awful than I feel. My eyelid is permanently surprised. My face has transformed into a shell-shocked gargoyle. And you can see the tape—it’s not invisible at all. It’s an off-white, pasty sticker just sitting on my skin.

I blink a couple of times. Maybe the tape just needs to adjust to my eye. But the more I move, the more its edges pinch and peel.

I’m an art project gone wrong.

Wildly, I rip it off. The tape leaves behind a red mark, a raging half-moon that could never conceivably be my eyelid crease. I sink to the tile floor, my handiwork now strewn around me. The bright red mark rests above my barely there monolids, cruel and relentless as it sneers: To think you could change. What a silly, silly girl.

Main Street Blues

“What’s that on your eye?”

Mom stops Main Street traffic to roll up her sleeves and poke at my eyelid. I swat her hand away.

“Mom, seriously, we’re in public!”

“Okay, okay.” She raises her palms in surrender.

“I probably just rubbed them too hard when I woke up, that’s all,” I mutter. It’s a bad excuse, but she’s no longer paying attention. She’s too distracted by Fleur’s mom, who’s just left Vesper’s Bookstore and is furiously waving at us.

“June!” Mom calls, putting on her fake Adult Voice.

June scampers to us in yoga pants, leaves crunching underneath her sneakers. “Beverly, Maxine, how funny running into you here!”

This town is five feet wide, I think. You literally run into everyone everywhere. Still, I smile and nod while June chatters endlessly about Fleur’s seventh-grade classes, her pet labradoodle, and regionals, of course, which, can you believe it, are only a week and a half away. While Mom attempts to make small talk, I stare out at the mountain-dappled skyline. The cobblestone sidewalks are scattered with tourists. By December, they’ll be teeming. To live up to its reputation as a winter sports wonderland, Lake Placid always pulls out all the stops with toboggan rides and snowshoeing, warm cider, and twinkle-light shops jingling with ornaments to take back to the city. American flags line the lampposts as if to alert every visitor that we are the pride and joy of United States athletics. I touch the mark on my eye. An all-American town.

“Anyway, I’ll see you at the rink later,” June finishes. “Phil’s got a hockey game, and then Fleur has practice, so I’ll be there all day. Lucky me!” Her hollow laughter echoes in my ears.

Mom touches June’s shoulder in a way that seems friendly, but really means Bye now!

“Absolutely,” she says.

When June is out of sight, Mom shakes her head. “That woman could talk my ear off.”

We stop in front of Bob’s Skate Shop and swing open the door. It’s the only skate shop in town, but it’s verifiably the best in New York. I always try to get my skates sharpened ten to twelve days before competitions. I don’t want to skate on dull blades, but I also don’t want to experience any new sensations during my performance. Everything should feel exactly like I’ve practiced.

Bob comes out from the back with goggles strapped over his hair. He looks like Dr. Frankenstein.

“My two favorite people!” he exclaims.

“Good morning,” Mom says, gently removing the skates from my bag.

He scoops them into his arms like newborn infants, already knowing what I want before I’ve even asked.

“I’ll be back in ten,” he says.

Mom smiles. “Such a pro.”

Ten minutes is totally enough time for me to start the math homework crumpled in the bottom of my backpack. Mom always makes me bring homework everywhere I go because I never have enough time to do it. But math is hard and terrible, so I immediately pretend to be really invested in the new skate guards hanging in rainbow colors down the wall. Mine are boring and black, but these come in shades like “silver spiral” and “layback lilac.” My personal favorite is “tangerine tango,” a flashy orange that would pair magnificently with a gold medal around my neck.

I dangle my choice in front of Mom’s face.

“Can I get these?”

Mom pushes her hair behind her ears and looks down at me with exhausted eyes. She’ll never admit it, but she gets just as restless as I do before competitions. I know she wants all my hard work to pay off.

She flips over the tag and looks at the price.

“No, Maxine.” She sighs, pacing between the apparel and accessories aisles.

“Pleeease?” I say, knowing I shouldn’t.

Mom snaps her head toward mine so quickly, I hop backward.

“Maxine, we’ve already spent loads on your other stuff.”

I pout, following her eyes as they trail down my Patagonia parka; fleece-lined, over-the-boot skating pants; and Zuca figure skating bag waiting patiently by the register for my freshly sharpened skates. My costumes sit in my closet at home, one elegant and black to match my sleek short program, the other light blue with tiny jewels running down the center. As Judy would say—delicate but beautiful.

Dad always reminds me that money doesn’t grow on trees, but it’s easy to forget when you’re clutching tangerine tango skate guards that bend like new rubber. I loosen my grip. I don’t even really care about them anyway.

“Sorry,” I say. “I know.”

Mom ruffles my hair. The whirring stops. Bob reemerges, shiny skates in hand.

“All set, kiddo.”

I grab them by the laces, marveling at their metallic shine. Slowly, I run my finger along the edges. A rush of excitement floods my body. I can’t wait to get on the ice.

Bob rings us up, and Mom fishes for her wallet in her purse, emerging with her credit card. She slides it across the table.

“Before practice, you’re doing your math homework,” she says without looking up.

I groan.

“Don’t think I didn’t notice.”

I sling my backpack over my shoulder and roll my skate bag toward the exit.

When I make it to the Olympics one day, I’ll earn a bunch of money from endorsements and Stars on Ice and stuff. Then I won’t have to do math or school or any of that boring junk. I’ll become rich and famous. And I’ll pay Mom and Dad back for everything.

Dress Rehearsal

Five days later, I dangle my arms across the boards and watch the Zamboni’s sharp blades shave off a thin layer of old ice, leaving a perfectly smooth surface behind. I love being the first to skate across the clear-as-glass surface—it feels like I can do anything. As the driver finishes up, I pop off my guards, ready to skate. Judy holds me back.

“Not yet, Maxine. Hollie’s first.”

On the sidelines, Hollie dons a cotton candy dress over her tights and becomes a pink blur as Viktor counts her jumping jacks. In the days before a big competition, we each get individual time to rehearse our free programs. Of course Hollie gets to go first.

“Fine,” I mutter.

Hollie from Virginia bolts onto the smooth ice, ruining it with her blades. She moves into starting position and nods to the audio guy. “My Heart Will Go On” echoes through the rink. Usually, we have to play our music on our own speakers so everyone can hear their programs, but now, with only Hollie on the ice, the Titanic anthem croons from the PA system. I crinkle my nose.

“Celine Dion is a little cheesy, don’t you think?”

Judy nudges my ribs. “Be nice.”

Fine. But just because Hollie is skating, it doesn’t mean I have to look. Instead, I throw my leg up on the boards and stretch out my hand to touch my toes. Then I move into spiral position, pointing my foot as far as it ca

n go. I imagine I’m Michelle Kwan performing her signature spiral curving down the ice. I swing my arms back, a smirk toying with the corners of my lips. Who needs Hollie when you’re the greatest skater of all time?

Viktor’s interrupting screams and rapid hand movements aren’t helping, though. Okay, fine, I’m looking.

Hollie ends her skate with a scratch spin before flinging her arms across her chest in a melodramatic embrace. The music cuts off and Viktor cheers so loudly, he might just crack my eardrums.

“Six out of six!” he shouts.

I want to remind him that the judges don’t score out of six anymore, but whatever.

Hollie skids off the ice and gives me a huge braces-filled smile. This time, her rubber bands are pink. Of course. They match all the loooooove she’s emoting on the ice.

“Have a good skate, Maxine,” she says as she waltzes past me, Viktor on her heels.

“Yeah, thanks.” I fight the urge to roll my eyes.

I do a lap around the rink as Judy yells to keep my arms steady in the air.

Yup. No time for flapping wings now. This is crunch time.

“All right, let’s do it.” She gives me a thumbs-up as I glide to the center of the ice.

Just give it your all, Maxine.

The opening fluttery piano scale curls through the rink speakers. Gershwin’s Concerto in F is my favorite. It’s classy and sassy, two things I strive to be as a skater and a person. I first heard it when watching a rerun of Yuna Kim’s 2010 Olympic gold medal free skate. She’s a Korean skater whose grace and elegance are unparalleled. I can’t match her artistry, but maybe through this program, I’ll hint to the judges that I can get there someday soon.

A homage to Queen Yuna’s subtle cheekiness, I begin my program by blowing a kiss to the air before three-turning into twizzles across the ice. They seem simple, but if you falter just the littlest bit, you could tilt and fall on your butt. This time, though, my twizzles are so clean, I could be an ice dancer.

Maybe it’s Hollie’s irritatingly good skate etched in my memory or the red welt still imprinted on my eyelid or the newly sharpened line of my skates slicing the ice, but I am fired up and unstoppable. Double Axel? No problem. In fact, I get so much height that I’m practically bungee jumping into the air. Double Salchow, double toe—a breeze. Triple toe—check. I transition from a layback into a Biellmann spin, one of my newest elements. You lift your blade behind your back and then all the way up over your head. Then you somehow spin while holding this position. It seems like an impossible move, one which requires inhuman flexibility. But I’ve been stretching at the boards twice a day before practice. At home, I clutch my bed frame and arch my back until my head reaches my foot. Tip as far as you can go, I tell myself. Don’t be afraid. And I’m not—I’m fearless. I don’t even feel the usual ache in my spine as I turn in ice-carved circles.

I almost forgot how beautiful spinning blades can be, how the wind that I create as I twirl through the rink swirls like magic. Time seems to float by. Double Lutz, double loop. Camel spin. The piano crescendos. Sit spin.

My blade cracks against the ice. Arabesque. Double flip. Now everything melts away: Alex, Ms. Valencia, and Korean eyelid tape. Only my blades, only the rink exist. I end my program with an arm lifted above my head as the music fades to silence. I am weightless.

And also really out of breath. I suck in air and search the rink for Judy. That last spin made me so dizzy that the whole world seems to be in motion.

Judy skates over to me from the boards. Her face is all pink, her eyelashes clumped together in wet bunches.

“Coach,” I half laugh, half gasp, “are you crying?”

“Be quiet,” she says, wiping away tears.

She cups my face with her gloves. “Maxine Chen.”

Oh no. My full name, that can’t be good.

Judy shakes her head.

“No matter what happens next week, you should know that you’re a terrific skater. I’m so proud of you.”

My body is doing invisible somersaults.

“Oh man, Coach,” I say. “Don’t make me cry, too!”

A Revolution

At school on Friday, I bounce to my locker, humming along to Gershwin, still on a high from my all-time best practice. I glance at my reflection in the mirror inside my locker door. In the glass, I catch Alex and Victoria chatting several feet behind me. She’s clutching her science binder—the one we decorated together with magazine cut-out letters and YOU GO, GIRL! stickers from her mom’s craft drawer.

Alex leans in and whispers in her ear. What on earth could he have to whisper to Victoria? Probably something stupid, like “I’m failing math,” or “I accidentally dumped an entire bottle of gel in my hair this morning.”

Nope. I shake my head. You’ve got better things to think about. Like how I’m going to slay this competition on Saturday. I look back at the mirror, studying the freckles splattered across my cheeks, the red mark on my eyelid now a faded line, practically invisible. I stuffed the eyelid tape in the bottom of my bathroom drawer, and I plan on never letting it see daylight for the rest of eternity.

Still, as I glance at myself in the glass again, I can’t help but examine the flat ridges of my skin, the way they curve over my lids so that all you can see are my short eyelashes peeking out. I inhale sharply. It doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter.

I slam my locker shut. Usually Victoria walks with me, but of course, she has other friends now. I roll back my shoulders and strut down the hallway. Whenever I’m dragging my heels, Dad always tells me to keep marching. Who needs Victoria when I’m not only capable of marching to class but parading to regionals and kicking butt on the rink?

When I arrive, I slide into my seat and bury my nose in my history textbook, catching up on last night’s chapter that I fell asleep reading. When the bell rings and everyone files in, I pretend to not even notice Alex drumming his pencil against his knee in the back of the room.

Our history teacher, Mr. Warren, sits hunched over an egg sandwich, engrossed in some novel. I squint: Catherine the Great: Portrait of a Woman. It’s always the same routine with him—egg sandwich, thick biography, funky round glasses. The only thing that changes is the color of his spectacles; he loses them so often, he buys a new pair about every other week. Today, they’re a mossy green.

“All right, everyone, quiet down!” he says to an already mostly silent classroom. Flecks of egg have settled in his mustache.

He turns to the whiteboard and writes in fat letters: REVOLUTIONARY WAR.

Half the class groans. “There are so many “wars,” someone says.

“Yes,” Mr. Warren says, “and there are many more to come.” He pauses. “Now who can tell me about the Revolutionary War?”

Elisa, a girl with red hair in two high pigtails, shoots up her hand.

“It’s when the Americans won their independence from the British.”

“Correct!”

Mr. Warren wipes a hand across his eggy mustache and begins writing furiously on the board. I stifle a yawn. We already went over this in fourth grade. This is baby stuff. Thomas Jefferson, the Declaration of Independence, Washington crossing the Delaware, blah, blah, blah. There were the redcoats and the colonists, and stuff about taxation without representation, and a bunch of white guys having a tea party while dressed up in problematic Native American costumes. I remember that Mom volunteered to help me study for the test on this topic, but instead of going over the flash cards I’d made, she kept going on long tangents about power and privilege and the symbolic importance of the Boston rebels dumping tea into the harbor. Honestly, if she weren’t a pharmacist, she’d be a great politician.

I peek at the board. Mr. Warren is still scribbling, but I can make out some of the words behind his head.

Crispus Attucks. Henry Knox. Mercy Otis Warren. Moses Brown. Abigail Adams. Roger Sherman. John Paul Jones.

He whirls around, arms crossed against his paisley button-down.

/> “Now,” he says, “who recognizes any of these names?”

Silence. Someone sniffs. I can hear Alex rolling his pencil back and forth against his desk.

I bite my lip. Well, maybe I don’t know everything about the Revolutionary War.

Mr. Warren smiles triumphantly.

“That’s what I thought.”

He returns to the whiteboard, underlining names.

“A lot of people know about the big players in the Revolutionary War, but most don’t know about the unsung heroes. These are just a few of them.”

Mr. Warren walks to his desk drawer, pulling out a fedora. He makes a show of waving it in the air. Mr. Warren is like the Adam Rippon of teaching—ever entertaining, although Adam never has an issue with egg-sandwich shrapnel.

He scoops up a bunch of little pieces of paper from the desktop and drops them into the hat.

“This month, we’re going to be putting on skits.”

“Skits?” Alex cries.

I crane my neck to see Alex groaning from the back of the room, his spit spraying across Elisa’s desk.

Elisa gags, rolling down her sleeve and wiping it along her desk’s rim.

“Yes, skits.” Mr. Warren grins. “You’re each going to pick a name from this magical hat”—he holds out the fedora like a cauldron—“do some research on your unsung hero, and then write up and perform a short skit for the class from the perspective of your historical figure.” He pauses. “I’ll give you step-by-step instructions after you choose your figure. We’ll be working with Mrs. Lovell, the librarian, on best research practices.”

He moves down the rows. Hands fumble in the fedora and emerge with scraps of paper.

“I suggest writing down the names of your unsung heroes on your phones, your planners, your foreheads, whatever,” Mr. Warren says. “I know how easy it is for you kids to lose things. And forget things.” He winks at Alex. “And I don’t want any excuses for missed work.”

Following Mr. Warren as he weaves down the aisles, I watch as Alex shrinks down in his chair.

The Comeback

The Comeback