- Home

- E. L. Shen

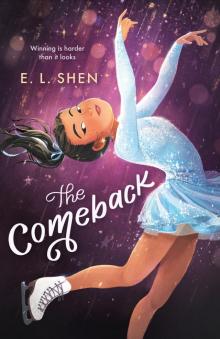

The Comeback Page 7

The Comeback Read online

Page 7

Isn’t that Fleur’s mom over there? Go talk to her and distract yourself.

Don’t change the subject.

Okay, fine, I’ll check. Jeez.

Wait, was my triple toe fully rotated? No, I won’t fall into this trap. I keep my eyes on the monitor. Shawn Mendes screams through the speakers. They always try to distract the crowd with punchy music while the judges compile the numbers. As much as I love his songs, his belting feels like earsplitting squeals now.

Is this how Karen Chen felt after her long program at the 2018 US Championships? Her performance defined whether she or Ashley Wagner would make the Olympic team since Bradie Tennell and Mirai Nagasu were in first and second. I picture Karen in her all-black ensemble, defiant red lipstick, a giant burgundy flower pinned to her bun, as if to say: I’m better. I’m stronger. I’ll clinch this spot. And she did.

I square my shoulders. I’m better. I’m stronger. I’ll clinch this spot.

Numbers flash onto the monitor below my feet. A disembodied voice thunders over the PA.

“The scores, please, for Maxine Chen.”

Judy squeezes my hand.

“For her performance, she has earned a score of 72.56 for a total score of 105.57. She is currently in second place.”

My hands fly to my mouth and I fight the urge to jump to my feet. I can hear Mom shrieking with joy and sense Dad’s fist flying into the air. Judy throws me into a giant embrace.

“You did it, girl. You’re going to sectionals!”

I’m going to sectionals. I, Maxine Chen, am going to SECTIONALS. Tiny tears trickle down my cheeks. Sometimes, there are happy cries in the Kiss and Cry.

Cannon Fire

There should be a rule that after a big competition, I get the whole following week to lie on my bed, limbs outstretched like a starfish, and do absolutely nothing. Mom, unfortunately, does not agree with me. On Monday morning, she makes me do my usual twenty crunches and then pushes my very sore legs out the door and down the hill to school. Now I’m sitting in the library yawning every three minutes while blinking at a computer screen. At least I got to sleep in. Judy said I deserved a three-day break from morning practice. This is the first morning in months that I’ve woken up on a weekday with the sun streaming through my window.

Mr. Warren is rattling off a series of best research practices, but his voice crackles against my ears like radio static. I look at my fingertips. I can still feel the touch of the cool pewter of the fourth-place medal, now proudly hanging on a hook in our living room next to a Polaroid Dad snapped from my free skate.

Hollie won gold, like I knew she would. She really did skate beautifully. I still stand by the fact that Celine Dion is cheesy, though.

Crack! I am jolted out of my daydreams by what sounds like someone taking a fist to their keyboard. I turn, the ice and Celine Dion melting before my eyes. Instead, I find Alex pounding on his keyboard—a library performance for the boys laughing beside him.

I glare as he smashes the keys, a heavy-bellied snort escaping from his lips. Today, his spiky hair situation is at an all-time high. Literally. I am convinced that there’s a porcupine growing on his head.

I wish I could tell him how stupid he looks, how infantile, but my body still feels small and empty around him. Instinctively, I want to curl into a corner.

“Alex Macreesy,” Mr. Warren’s voice thunders, jumping by six decibels, “have you ever heard of the phrase, ‘You break it, you buy it’?”

Alex glances up at Mr. Warren’s puffed-out chest.

“Huh?”

“You break it, you buy it,” Mr. Warren repeats, stepping forward. “If you break that keyboard, I will personally send your parents the bill. Understood?”

Alex’s cheeks turn the color of ripe strawberries. He slumps down in his seat, his porcupine head drooping. I didn’t even know Alex had the capacity to feel embarrassed. The realization almost makes me feel powerful, strong. Laughter builds, bubbling up to my nose. I can’t help it. I let out a snicker.

Alex’s eyes whiz toward mine, sharp and ugly. His face is still blotchy, but his fists ball up like he’s waiting to punch me in the gut. Okay, I totally take back that snicker now.

Mr. Warren turns around to help Elisa. Alex’s friends squirm in their seats, pretending to be thoroughly engrossed in their research. I try to focus on my computer screen.

Paragraphs on paragraphs about Mary Ludwig Hays loom before me. I yawn. Why is she important again?

I scroll through a couple of articles, too lazy to move my hand from the mouse and read anything. Then I stop. In one illustration, there’s a battle scene showing a woman with curly brown hair stuffed under a cap, soot covering her cheeks, shoving a cannonball or something into the mouth of a cannon. Soldiers have fallen on the scorched grass beneath her feet. In another, she’s shown jamming some kind of pole down the barrel. Whatever it is, she definitely knows what she’s doing with it. The caption below the painting says: A depiction of Mary Ludwig Hays at the Battle of Monmouth.

I keep reading. At the Battle of Monmouth in June 1778, Mary Ludwig Hays helped the soldiers by offering them water and supplies. The weather was extremely hot. Mary’s husband and fellow soldier, William Hays, collapsed during the battle. As he was carried off the field, Mary quickly took his place at the cannon and continued to “swab and load” using her husband’s ramrod. During the battle, a British cannonball came right at her and tore off part of her skirt. She is believed to have responded, “Well, that could have been worse,” and carried on fighting.

There are more images of Mary with a giant wheeled cannon, fiercely concentrating as the other men around her battle on, an American flag billowing in the background. After the war, George Washington apparently honored Mary by officially making her a noncommissioned officer. From then on, she went by her nickname, “Sergeant Molly,” and was called that for the rest of her life.

I stare at the computer, eyes fastened to Mary’s torn skirt and clenched fists, her determination as she defied expectations and fought the British. I know exactly what scene I’m writing for the skit. Maybe Dad can build me one of those cool cannon-blaster things. I cock my head at the giant wheels that probably would be as tall as I am. Well, I don’t know how we’re going to make those. But details, details.

“Psst, Maxine.”

Mitchell Hawkins smiles at me from behind his mass of red hair. I glance at him, and then at the other two boys also looking at me, their necks craned my way. In the middle sits Alex. He’s grinning at his computer screen, which is tilted my way. And then looking straight at me, he presses his index finger on the keyboard button to scroll down to a message that fills his screen in huge bold font.

MAXINE

IS A

NERDY

CHINK!

Mitchell and Alex and the other boys start cracking up, covering their mouths with their hands to stifle their laughter. I wish I could be somewhere else. Anywhere else.

Mr. Warren senses the commotion from across the room and stands up. Alex whips around in his seat, quickly deleting all the evidence. It’s as if his words never existed, even though I can’t stop seeing them.

Keep it together, Maxine, I try to tell myself, but the words nerdy chink ring in my ears until I’m nauseous.

Alex and his friends are still laughing as they zip up their backpacks.

The bell rings.

I am not a nerd, I think, I am not a nerd, but I am a chink. I am a chink. I am—

I clench my eyes shut and think hard about Jennie, cooler and smarter than everyone in this stupid room. I focus on her perfect smoky eye shadow, chin held high, Asian and proud. I try to imagine myself that way, like I felt that moment wearing purple eye shadow, staring into her compact mirror. But I can’t find that Maxine. She’s not here right now.

I open my eyes. Purple eye shadow can make my eyes pop, but it doesn’t change who I am. Not to Alex, at least.

And maybe not even to me.

Pretendi

ng

“There’s my sectionals lady!”

Mom swings open the car door, cupping my flushed cheeks in her hands. I tumble inside. After school, I walked to the rink and did Lutz after Lutz until I couldn’t anymore. Thankfully, Judy was busy helping Sam with his sit spins and Fleur was moping about her fifth-place finish, so no one bothered me today. In the silence, I flung my body into the air until Alex and the computer screen and the flashing words disintegrated beneath the ice.

But now, looking out at the shadow of mountains curved beneath the skyline, the whole day floods my mind once more. I avoid Mom’s abundant cheer as I buckle my seat belt. The car ride home takes only a few minutes, so at least I won’t have to endure her giddiness for too long. Mom turns on the stereo. Sappy string music blasts from the speakers and Teresa Teng’s tinny voice fills the car. She’s singing something in Mandarin I can’t understand.

“Can you turn that down?” I grumble.

Mom raises an eyebrow.

“Sure,” she says, adjusting the dial, and then: “What’s with the mood? Was everyone at school happy for you?”

Ha. Like I told anyone at school about regionals.

“Yeah, Mom, they were.”

“Victoria must be so proud of you.”

When Victoria’s not clinging to Alex, she’s flocked by theater kids anxiously discussing this year’s musical. This morning, I could hear her shriek from twenty feet away when she looked at the cast list and realized she got the role of Nancy in Oliver! Little does she know that I peeked at the list, too, just to see if she nabbed the part. Not that I’m going to congratulate her or anything. She doesn’t even acknowledge me in the cafeteria anymore.

“Uh-huh.”

“Do you have a lot of homework to catch up on? Is that it? You know Dad and I can help you.”

“No, I’m all set.”

“And practice? It went well?”

I look out the window. “It was fine.”

Mom sighs, weary eyes on the road as she turns onto our street. Teresa’s voice, now quiet, runs up the octave.

“Okay,” Mom finally says.

I know there is so much she wants to say. There is so much I want to say. But if I tell her anything, she’ll call the principal or the superintendent or—knowing her—ring up the PTA and give all the parents a lecture, and then I’ll be the laughingstock of Mirror Lake Middle School. Maxine called her mommy because she couldn’t deal with a little teasing. I can just hear their cackles now. I can just see Victoria and Alex, arms linked as they skip down the hallway, shaking their heads at stupid, nerdy Maxine. The chink.

As we turn into our driveway, Mom studies my face.

“You’re sure you’re okay?” She taps my chin and smiles.

I force myself to smile back.

“Yeah,” I tell her, “don’t worry.”

A Little TLC

On Friday after school, Hollie shows up on my doorstep wearing pajama pants covered in little orange pumpkins and a Skater Girl sweatshirt. Her wavy hair is piled on top of her head in a messy bun. She points to her bottoms.

“’Cause of Halloween on Sunday. Get it?”

I swing open the front door a little wider to reveal my own skeleton sweatpants and black cat slippers. We both smile.

It’s kind of insane that my former archnemesis is legitimately standing in my foyer right now, looking around at photos of my family, snapshots of seven-year-old me in flouncy costumes and too much lipstick, proudly showing off my medals. Most of them are silver or bronze. I bet all the ones in Hollie’s house are gold.

I take a deep breath. Mom gave me a whole lecture this morning about collaboration, not competition, and keeping rivalry strictly on the ice. Then she went into some whole long story about this girl she used to hate who was her opponent in badminton and how they grew up and became friends and went to each other’s weddings, blah, blah, blah. Sometimes, I think Mom tries to wear me out just by talking a lot.

Anyway, I figure that Nathan Chen and Yuzuru Hanyu are always pitted against each other in competition, and they’re both nice to each other. Or at least, they compliment each other during press conferences. So maybe I can do this, too.

Hollie follows me into the kitchen. My eyes immediately jump to the little Buddha nestled in the corner by the jar of chopsticks, and the scroll on the wall Dad inherited from Grandpa that says a bunch of Chinese proverbs I don’t understand. When Victoria came over last year, she told me that my house smelled weird. What if Hollie goes back to the rink and tells Fleur and Sam and everyone else that my house is a total freak show? I swallow a lump in my throat and remember to breathe. To calm myself down, I play Would You Rather in my head:

Would you rather Hollie or Victoria be here?

Hollie or Alex?

I think about his stupid porcupine head.

Hollie. Definitely Hollie.

If Hollie thinks anything about my house, she doesn’t show it. Instead, she gravitates toward the brownie mix Mom left on the counter for us, cradling the box like a newborn baby.

“Chocolate fudge brownies are my favorite,” she says. She’s practically jumping up and down. It’s like she’s never seen brownie mix before.

“Cool,” I say, “let’s make ’em.”

While the oven preheats, I grease a baking pan, and Hollie dumps the mix into a bowl and adds oil and water. As she stirs, I squeeze in the little packet of fudge. I have no idea what to say to Hollie, who keeps sniffling and quietly humming to herself. The silence is earsplitting. I can literally hear Mom flipping magazine pages in the living room.

I scoop an egg out of the carton, trying not to break it. Hollie concentrates intensely on our concoction, her mouth moving quietly. Notes escape from her lips.

I freeze, about to crack the egg against the rim of the bowl.

“Are you singing … ‘No Diggity’?”

Hollie’s head shoots up, her face bright pink.

“Uh,” she says, “no?”

I shake my head at her. “Yes, you are!”

“Okay, I know it’s weird,” she blurts, “but I just really like the old stuff. Like Destiny’s Child, and the Spice Girls, and Usher, and all of that because I went into a Beyoncé black hole one time and just became really invested.”

She smooshes her hands against her cheeks and stares at me with worried eyes.

“Don’t laugh at me.” Then her expression changes. “Wait, how do “you know that song?”

A smirk tugs at the corners of my lips. “Ummmmm, I also love nineties music.”

“You do?”

My singing voice sounds like a cat wailing, but I manage to croak out the first few lines of TLC’s “No Scrubs.”

Hollie smiles so wide I think I can see every single one of her braces. She shimmies as I sing, bopping her shoulders up and down and twisting her arms like spaghetti. I let out a snort.

“You’re kind of weird,” I say between hiccups of laughter. I crack the egg open and add it to the mix.

Hollie sticks out her tongue at me, turning back to the bowl and the batter.

“So are you.”

A Light Bulb Goes Off

One kitchen karaoke session of all the Spice Girls’ greatest hits later, we bring our baked treat upstairs and sprawl out on my bedroom floor. Hollie stretches her pumpkin pajama legs and hops to her feet, checking out my spinner and weights and every poster covering my walls. She points to Nathan Chen on the ceiling.

“I like this one the best.”

I nod, cross-legged on my paisley rug. I mean, who wouldn’t want the first and last thing they see every day to be the ever-perfect Nathan Chen with his easy smile and dozens of medals?

Hollie sighs. “His hair is so floppy,” she says.

“Agreed.”

She moves to my desk, eyeing the algebra homework scattered across its surface, the Quiz Bowl participation ribbons haphazardly pushpinned to the bulletin board. Her shoulders sag.

“I wish I were in schoo

l,” she says, like she’s wishing for a trip to Disney World or Hawaii instead of a visit to hell on earth.

I sit forward, wiping brownie crumbs onto my leggings.

“You don’t go to “school?”

Suddenly, this majestic life billows before me, one without stupid boys and friends that are no longer your friends and lockers and homework you can’t finish because you don’t have enough time. No wonder Hollie is nailing her triple-double combinations. I would, too, if I didn’t have to see Alex Mac-greasy-face every day.

Hollie shakes her head. “Well, sort of. I’m homeschooled.”

“Oh,” I say.

No wonder she doesn’t have any friends.

Hollie plops back onto the floor, tucking her ankles under her thighs. She looks almost … sad.

“Have you always been homeschooled?” My voice comes out in a whisper.

“No,” she says, “not until skating became really intense. Then Mom pulled me out to focus on competing.” She traces a flower on my rug. “It’s been almost four years since I’ve been in real school.”

“Wow.”

Hollie shrugs. “It’s okay. I mostly just do workbooks and they’re pretty easy.” She pauses. “It’s just a little lonely, you know? My younger brother is two years old, so there’s not really anyone for me to talk to.”

“Well, aren’t your parents around?”

“Only my mom,” Hollie says, “and she can be … a lot.” Hollie turns her face toward the window. “She really wants me to focus. To work hard and get to nationals. And when I’m old enough, the international circuit. And then one day … well…”

Hollie holds out her arms like she’s trying to contain the entire world.

“The Olympics,” I finish.

“Yeah. The Olympics. I guess it’s just a lot of pressure.”

She glances back at me, her eyes scanning my face, searching for understanding.

“I get it,” I say, but I don’t, really.

I do want to go to the Olympics, but it’s a want, not a need. For Hollie, it seems different. I think about Mom and Dad, always worried that there’s too much on my plate, assuring me that I can quit when I want to, insisting that I work hard but also make time for fun. And brownies. I sink my teeth into chocolaty fudge.

The Comeback

The Comeback